Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

A defining trait of the current mortgage market could be creating a systemic risk that is entirely different from the 2008 housing meltdown.

In the past decade, many banks have transitioned out of direct government and conventional mortgage lending and servicing in response to stricter oversight from federal regulators, reputational damage and what they see as unclear origination and servicing guidelines. That leaves nonbank lenders dominating mortgage lending today.

The shift could put government entities like Ginnie Mae at risk if these nonbank lenders fail, which is one reason the Federal Housing Administration is putting together a plan to lure more banks back into the business, in hopes of mitigating the risk.

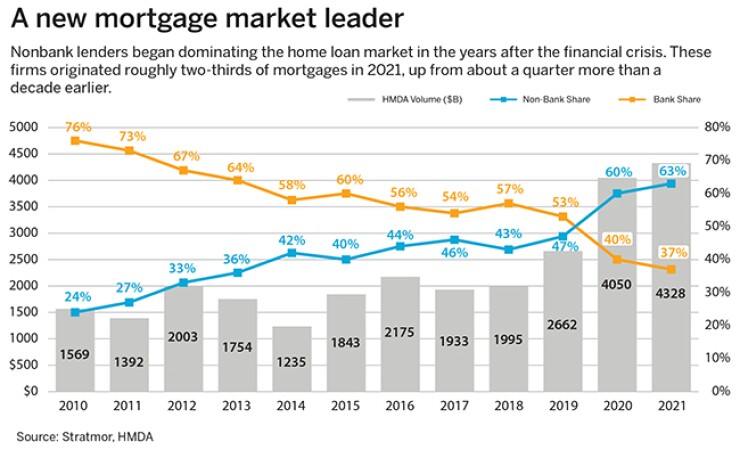

The latest tally, from 2021, shows that the share of banks participating in mortgage lending dropped from 76% in 2010 to 37% in 2021. The FHA’s program, specifically, was ted en masse.

This reality has always been acknowledged, but the concern has intensified.

The impact of banks’ departure “has been relatively limited because so many nonbanks stepped in to fill the void,” said Laurie Goodman, institute fellow at Urban Institute. “However, with origination activity way down,” the number of nonbanks will likely go down “and we’ll have a fair amount of consolidation in this industry. And my question is what happens next?”

Nonbank mortgage companies are generally monoline institutions, with no other business lines, and as rising interest rates dry up their purchase and refinance originations, some are closing shop. The main concern among former government officials, trade groups, and industry stakeholders is how Ginnie Mae, the guarantor of government mortgage-backed securities, will be affected if a critical mass of them go out of business.

Alanna McCargo, president of Ginnie Mae, acknowledged the “challenging mortgage cycle” and expects “consolidations as independent mortgage banks experience financial stress.”

This “impacts not only Ginnie but the entire ecosystem, especially with the concentration of nonbank servicing of government mortgages,” McCargo said.

If the downward trend continues to rock nonbanks and servicers, the government guarantor may be pushed to seize the servicing from failed companies, so it can transfer them elsewhere. This recently happened with part of the bankrupt Reverse Mortgage Funding’s loan portfolio. Some wonder whether that’s a function that Ginnie Mae could logistically handle on a major scale and whether it could hurt the agency’s mission to inject liquidity into federal housing programs.

But an antidote may be around the corner, which could partially offset some industry concerns and bolster stability for Ginnie.

For years, stakeholders have been calling on the FHA, which insures the majority of loans that Ginnie guarantees, to make changes to its origination and servicing taxonomy in ways that would bring back banks. Julia Gordon, FHA commissioner, has confirmed that changes to the latter are on the way.

The current composition of stakeholders participating in the mortgage origination space is drastically different from pre-2008. Nonbanks today make up a 91% share of originating Ginnie loans, up from 38% in 2013, and close to a 70% share of originating conventional loans, the Urban Institute’s October analysis found.

This new world order in the mortgage lending ecosystem — where nonbanks are the majority — has yet to face a market contraction as big as the one it is facing now.

“Nonbanks have yet to really feel a crunch,” said David Stevens, CEO of Mountain Lake Consulting and a former FHA commissioner. “Most of the nonbanks grew post-2009 into massive entities and now they’re all facing the biggest contraction that they’ve ever experienced in their corporate careers.”

The list of mortgage companies that have closed lending channels, exited the market altogether, or declared bankruptcy grows daily. In the past six months, lenders such as Freedom Mortgage, Mr. Cooper, loanDepot and Home Point Financial have all announced rightsizing measures, as lower margins have cut into their profitability.

Some banks, like Wells Fargo, have partly divested from the mortgage space, and while they also have other consumer finance businesses affected by high rates, they tend to have more diversified portfolios that could absorb the shocks better than nonbank lenders.

Diminishing depository participation in the mortgage lending and servicing space can be blamed in part on punitive measures taken against depository institutions by the Department of Justice and the Department of Housing and Urban Development following the Great Recession.

Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, SunTrust and Wells Fargo were among a handful of banks penalized for violating the False Claims Act, a federal statute originally enacted in 1863 in response to defense contractor fraud during the American Civil War. The law’s aim is to prevent companies from defrauding the government.

All in all, depository institutions had to pay more than $4 billion to the Justice Department and HUD for false claims in connection with underwriting, origination, and quality control practices on loans sold to the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as well as loans insured by the FHA.

Additionally, some of the same banks reached a $25 billion settlement in 2012 with the Justice Department and HUD to address alleged mortgage loan servicing and foreclosure abuses.

“Everybody loves to hate banks,” said Ted Tozer, former president of Ginnie Mae. “They are always the bad guys. But from my perspective, since I worked for a bank, we did the best that we could. We were just overwhelmed with the amount of delinquencies in 2009, but there was nothing egregious.”

These punitive measures, alongside market volatility concerns, caused many depositories to rethink their participation in the lending business. The main impact so far has been an exodus from FHA lending. In addition, banks have opted to stay involved in the housing ecosystem by becoming warehouse lenders.

“To protect themselves, depositories have become big third-party aggregators now rather than originators,” said Paul Hindman, managing director of Grid Origination Services. “Behind every independent mortgage banker, you’re going to find a bank, so they haven’t really exited, they’ve just mitigated their risk.”

A clutch of nonbanks, including Rocket Mortgage, Mr. Cooper, Home Point Financial, Newrez, PennyMac and Guild Mortgage, did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The housing ecosystem is vulnerable at this point in time because of two issues.

The first is that banks — including Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo — hold the purse strings for most of the nonbank players, meaning they can opt not to fund them. And the second is that this dynamic will inevitably impact Ginnie Mae, some sources said.

“Banks still play a pretty substantial role in financing those nonbank institutions, and in that sense they are still involved in managing a type of risk in the system. That helps the system as a whole, but it is different from the direct credit risk of making the loan and managing the loan,” said Meg Burns, executive vice president of the Housing Policy Council.

The problem with this, according to industry stakeholders and former government employees, is that banks could decide not to grant lines of credit. If that happens, the system could seize up.

“Banks have the power to shut most nonbanks down and put them out of business,” Hindman said. “If you can’t move loans off your warehouse line, you get no cash. And these nonbanks don’t have huge liquidity and cash. They need to be able to do this.”

“Do you think that Rocket, United Wholesale Mortgage, Fairway or any of these really big companies operate without a bank?” he added.

Banks can decide at any time that their nonbank partners are too risky and decrease the amount of lending that they forward, former government officials said.

The recent troubles at loanDepot are an example of this. As origination volume plummeted in 2022, so did loanDepot’s financing capacity. The lender’s warehouse and other lines of credit dipped to $2.5 billion in the third quarter of 2022, down from $7.3 billion in December 2021, according to filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“To the degree that banks get to choose, ‘Do I want to back Rocket Mortgage or Freedom Mortgage or PennyMac, or not? That is why Ginnie has to worry so much about what happens in a market that contracts, and in a market where somebody goes under,” said a former FHA employee who asked to speak anonymously.

Unlike Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which buy and securitize loans from lenders, Ginnie solely guarantees that the funds coming from borrowers’ payments will be passed through to investors on a timely basis. In other words, Ginnie doesn’t manage the asset, nonbanks do.

This difference means Ginnie is vulnerable to a collapse of any entity if the agency can’t find another company to manage the loans involved, former government officials said.

In the past, the agency would turn to depository institutions to buy the assets if another lender was going out of business, said Michael Bright, a former Ginnie Mae chief operating officer and the current CEO of the Structured Finance Association.

“Most banks would happily buy” the mortgage servicing rights, Bright said. “But if the banks say we don’t want to be in that business at all and at the exact same time nonbanks can’t make their [principal and interest payments] … you put Ginnie Mae at risk for having to step in and make payment on everyone’s behalf, which is just exceptionally challenging and dangerous on an operational level.”

A lack of liquidity among issuers could push them out of business, and if there is no one to buy their assets, Ginnie will have to put the servicing books of nonbanks on its own balance sheet.

“Then Ginnie Mae would have to hire a subservicer to manage the operations of P&I calculation and it would be Ginnie’s financial responsibility to ensure that there was P&I,” Bright said, referring to principal and interest. “Ginnie Mae would then become all consumed with having to be a servicer and they wouldn’t be able to do anything else. They would really have difficulty managing other operational programs.

If “this giant bond guarantor is unable to perform its main duties because it’s too busy being a servicer, that would be a tragedy of that situation,” Bright added.

Tammy Richards, CEO of LendArch, said in a written statement that more instances will come to the forefront of Ginnie Mae having to seize servicing from companies, if nonbanks fail to quickly modernize.

“The companies that will survive will be those with the best strategies for efficiency,” Richards said. “Those that are prepared will be able to withstand this roller coaster, but this is definitely not a blip, and action is necessary to succeed.”

Another scenario that could unravel in this shrinking margin environment is a lag in principal and interest payments being forwarded to investors.

“When money comes in from the nonbanks and it’s not adequate to make P&I, the agency has to figure out how to quickly raise cash to make that P&I,” said Bright. “I can tell you firsthand that Ginnie’s relationship with the Treasury Department is not robust enough that they would know exactly what to do.”

Sammy Mayo Jr

However, McCargo, Ginnie Mae’s president, said the agency is taking steps to ensure the nonbanks’ financial stability.

“Ginnie Mae is in continuous contact with our issuers and is working productively with them on their business strategies during this time,” McCargo said in a written statement. “If industry conditions become more challenging, we will continue to seek ways to improve the financial resiliency of the independent mortgage banking sector.”

The agency has already taken steps to create guardrails by updating its counterparties requirements for nonbanks. But that has been so controversial that its implementation date has been delayed by a year, to the end of 2024.

Ginnie Mae also has added heightened supervisory oversight of issuers by having them present to the agency how they can handle stress scenarios.

However, that is “nowhere near the level of supervision that the Federal Reserve provides banks,” Bright said.

But something else may be around the corner that can inject more stability into servicing.

Banks are unlikely to become more active participants in the mortgage origination universe, specifically in FHA lending, sources said. Servicing, however, is another matter entirely.

“The banks are skittish on the origination side because of the false-claims issues that happened after the housing crisis, but from conversations I’ve had with them, they are willing to do FHA servicing,” said Brian Chappelle, founder of Potomac Partners. “The benefit of that is it will get them back into the Ginnie Mae program, which is good for Ginnie Mae.”

Different administrations have worked toward the goal of bringing banks back into the FHA program, in one form or another.

Under the Obama administration, the FHA published an origination taxonomy, which was meant to provide greater clarity and transparency to banks about participating in the program. Additionally, a memorandum of understanding, signed by HUD and the Justice Department, was enacted during the Trump administration. This set prudential guidance on the appropriate use of the False Claims Act.

However, that did not move the needle in the favor of the banks returning to the FHA program.

“I think there’s still some residual concern,” said Pete Mills, senior vice president of residential policy and member engagement at the Mortgage Bankers Association. “The memorandum of understanding between HUD and DOJ is very helpful, but I think there’s some concern about how durable this reform is and whether it will survive.”

Banks also believe “there was too much reputational damage after the DOJ settlements,” Tozer said.

“If banks ever come back to originating or servicing they’re going to want to understand exactly what’s going on and they want to make sure that people live up to it,” he said.

Now the Biden administration is taking a stab at bringing banks back, this time by focusing on FHA servicing.

“We are turning our focus more to that servicing side,” Gordon said. “FHA would really like to be a partner to more banks, if we have the opportunity.”

A few things have been set in motion by the administration that are expected to come to fruition sometime in 2023, Gordon noted.

“We are creating a servicing taxonomy similar to one that was created on the origination side. And the status of that right now is that a draft was put out, we received a comment from industry stakeholders. And now we are working with those stakeholders to finalize that taxonomy,” Gordon said.

The administration is also looking across all of its servicing policies to align better with conventional standards, which some hope will reduce the costs of managing government loans.

Rulemaking is expected to take place over the next year, Gordon confirmed.

This will specifically address one of the biggest complaints that banks have with FHA servicing requirements — the foreclosure timeline and curtailment, and by doing so could make servicing government loans less pricey.

“We have heard concerns about our foreclosure timeline and curtailment, we are in fact looking at those, it is on our agenda,” Gordon confirmed.

There is optimism that these two changes will bring banks into being Ginnie Mae issuers.

“As we’ve gone through the process over the years, I think the taxonomy and the curtailment timeline are sort of two of the last reforms that we’ve been talking about for a long time and engaging with HUD on for a long time,” Mills said.

“So our hope is that these two things in particular would be the thing that would begin to bring banks back into government lending,” he added.